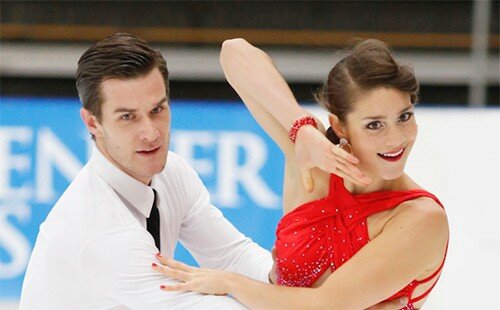

Canadian-born Laurence Fournier-Beaudry and Nikolaj Sørensen of Denmark had represented his homeland in ice dance since the beginning of their partnership in 2012. Danish citizenship laws are among the strictest in the world and from the outset both understood it would likely be impossible for Fournier-Beaudry to obtain a passport, which is a requirement to compete at an Olympic Games.

Instead, Fournier-Beaudry, 26, and Sørensen, 29, had focused on improving their World placement each season, with the goal of making the top 10. But when they earned an Olympic berth for Denmark with a 13th-place finish at the 2017 World Championships, not being able to go to the Games in PyeongChang brought a disappointment neither had anticipated.

“In the beginning we didn’t talk seriously about going to the Olympics because we never thought we could make it that far,” Sørensen said. “We just focused on our goal until 2017 Worlds when we learned the International Skating Union (ISU) rules permitted us to qualify a spot for Denmark even though we could not go.

“So, when we qualified, obviously it got a little closer to us. We got attached to it in a way that was hard to shake. I contacted the Minister of Culture in Denmark and he pretty much said there is no way, it will never happen. ‘It has never been done before and we don’t make any exceptions for anybody.’”

In the summer of 2017, the couple began discussing an alternate plan. “We decided that even though we were not going to the Olympics, we would train as if we were,” Sørensen said. “But as the Olympics got closer Laurence had a really hard time and cried a lot — more than me in the beginning. It hit me way later. So we both had waves of dealing with it emotionally, which was tough.

“Laurence and I had to figure out what we were doing next as Denmark would not be able to send us to the Olympics even if we did another four years. We spoke with our federation. They were really sorry about the situation and were so helpful but they said, ‘we can’t make this happen and at your level you deserve to be at the Olympics. So, whatever you need … we are going to help you to do whatever you feel is right.’

“After 2018 Europeans we spoke to the vice-president of the federation and our coaches. We decided that skating for Canada made the most sense. Laurence is Canadian, we train in Canada and I am becoming Canadian.”

Within weeks, the Danish federation had sent Skate Canada a release, but Sørensen said it was kept under wraps until after the Olympics.

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

Fournier-Beaudry began her sporting career in gymnastics before taking up skating at age 9. Her parents were recreational skaters and wanted her to learn. The Montréal native loved it from the first time she tried it.

She began taking lessons and when her freestyle coach suggested she try out with someone in ice dance, Fournier-Beaudry decided to give it a go. “I skated with a boy and got the passion right away to share the experience with someone else and not just be by myself all the time,” she recalled.

Sørensen began skating in 1996 at his father’s urging. “My dad wanted me to learn how to skate because he never had the opportunity. He lived in a city without an ice rink and had no place to skate except on a lake in the winter,” he explained. “At age 7, I went out on a lake and I could pretty much skate right away. My dad said that he really wanted me to learn if it was something I would maybe like to do. It took off them there.”

He began skating at a local club in his hometown of Copenhagen. Sørensen said the students were divided into teams and he was the only male on his. In 2001, an ice dance coach from the Czech Republic who worked at his rink suggested that Sørensen and one of the girls skate hand in hand and have fun “because you can also skate together.”

“Nobody really knew about ice dance in Denmark at that time,” Sørensen said. “There wasn’t really anyone who had done it other than the coaches who all came from Eastern European countries. So he got me into ice dance.”

After finishing high school, Sørensen decided to post his profile on Ice Partner Search. “Little did I know there were a lot of girls who were interested,” he said with a laugh. “One girl, Lili Lamar, (a former partner of Zachary Donohue) wrote me on a Sunday in May and asked if I could fly to New York the following Thursday. I thought well, if nothing else, I would just go to New York from Thursday to Sunday and have a good time and try skating.

”The tryout was successful and in August he moved to the U.S. The duo trained with Matthew Gates, who was coaching Kaitlyn Weaver and Andrew Poje at the time, and Sørensen said it was very exciting to experience living in that world. But four months later, Lamar quit skating.

With his second partner — Katelyn Good, a Canadian — he competed at two World Championships. In late 2010, Good’s mother asked them to move to Montréal, where she lived. “When we told Matthew we were moving to Canada, he said, ‘please go to Marie-France Dubreuil and Patrice Lauzon,’” Sørensen said. “They had opened their school in the fall of 2010 and he thought they could do a lot for our skating. He knew them when they competed and said he thought they had a lot to offer.

“We moved just before Christmas. It was a good decision because her mother passed away a few weeks later. Then my partner had surgery for a serious injury and it was all too much for her, so we parted ways.”

MEANT TO BE

In 2011, Fournier-Beaudry and her ice dance partner, Yoan Breton, were assigned to a Junior Grand Prix event in Romania. Shortly after 2012 nationals, Breton quit skating. “His objective was just to go out of Canada and once he had done that he said, ‘OK, I have achieved everything I wanted in skating and I want to end my career,’” said Fournier-Beaudry.

“I was looking for a new partner and doing some tryouts when I saw that Nikolaj was free. My coach asked if I could do a tryout with him, but he said he had already decided to skate with Vanessa Crone.”

Three months later, Crone quit skating. Out of the blue Fournier-Beaudry received a text message from Sørensen, asking if she could come to his rink the following day. “I was freaking out, I was so excited. I was asking, ‘what does it mean, what does it mean? What is going to happen tomorrow?’ The next day I arrived at the rink, got on the ice and Marie-France said, ‘Nikolaj and Vanessa are not skating together anymore, so we are going to start by learning the steps she had in the choreography.’ Then I understood that I was going to replace her. I was extremely happy.

“For about two or three weeks I didn’t really know what was going on, but I was training with him so that was a good thing. My friends kept asking if I was skating with him and I said, ‘I think so because I learned the steps of the choreography.’

Finally we sat down and Nikolaj told me he wanted to skate for another six years and that his goal was to be top 10 in the world. He said if I wanted to agree to this, then we could go on. It was my first year in seniors and I wanted to go to senior Worlds. So that is how we started.”

Fournier-Beaudry and Sørensen made their international debut in late 2013, winning medals at each of the three smaller events they contested. The duo placed 18th in their debut at 2014 Europeans and 29th at the World Championships. The following season they made a quantum leap up the standings, ranking ninth at Europeans, 11th at Worlds and captured silver and bronze at their two Challenger Series events.

CANADIAN ADVENTURE

When Fournier-Beaudry and Sørensen began training at the Montréal International Skating School, there were only four teams. They have been part of its evolution over the last six years and now more than 18 teams train with five full-time coaches.

Sørensen said they are the only ones who have been part of the transformation of the school from its early days to the present. “People wondered if there were going to be too many teams, but that is what is so great about it, it just kept growing,” he said.

Along with Dubreuil and Lauzon, Romain Haguenauer, Pascal Denis and his former partner, Josée Piché, and a ballroom teacher all work full-time at the school.

“It is a really friendly, positive environment. We are all trained to win so that creates something special,” said Fournier- Beaudry. “We all encourage each other so that makes it even more inspiring and everyone knows they are getting the best from the coaches on any given day. It is something cool to be part of and we are very grateful to be there.”

Sørensen said the young Canadian teams they train with have now adopted them as role models. “It is not only about us now, but also about the next generation and how we can help bring the juniors up. When we skated for Denmark it was really just all about us and though they supported us, now that we skate for Canada they are looking up to us as role models. It’s great to be part of that.”

Though neither skater had any direct contact with Skate Canada when the country change was taking place, they heard from their coaches that the organization was very positive and excited to have another top team on its roster.

In accordance with ISU rules on switching countries, Fournier-Beaudry and Sørensen must sit out one entire season to be eligible to represent Canada internationally. To set the process in motion as soon as possible, they skipped the 2018 World Championships.

Despite having to miss the first half of this season, they have continued to train every day. They plan to compete at small competitions within Canada this year, and will have to go through the national qualifying process to earn a spot at the 2019 Canadian Championships.

“It will be a new experience and we are both very excited about it. It is all so good,” Sørensen said. “It feels so humbling to be part of a team where you really have to pull your weight. It is not like skating for Denmark — not that that was easy — but we never had the pressure of doing nationals or stuff like that.”

The duo settled on “Adiós Nonino” by Romulo Larrea, for the rhythm dance this season. They found the music at the beginning of 2017, but their coaches suggested they do Flamenco and not a Tango last season.

“This year we went with the piece we wanted to skate to. Nikolaj really loves it and we are both emotionally involved in this music, so we decided to use it,” she said.

Fournier-Beaudry found the music on a CD in her father’s collection many years ago and was drawn to it the first time she heard it. Their music is a mix of three different versions: two instrumental and one vocal.

“Laurence cut the music. For the Tango Romantica she said we don’t just want only instrumental so she put some of the vocal part on top of the instrumental,” Sørensen explained. “She liked it better than the vocal version that had more piano, so all three versions are actually layered on top of each other throughout the program. Literally, the final versions of our music are the ones that Laurence cut.”

The duo then took the samples to music guru Hugo Chouinard. “Hugo is the master of sound and he cleans everything up,” Sørensen said. “If there is a beat missing here or there he has the equipment to add them in and make sure that the beats per minute are appropriate. Laurence made sure he understood all the cuts she made and how it was layered together.” They are keeping their free dance music from last season (“Spanish Caravan,” “Hush,” and “Asturias”), but have made radical changes to the program to comply with the new rules that will come into play this year.

“We are so much in love with that program. We felt it was growing so much and we did not have the time to get it where we wanted it to be,” said Fournier-Beaudry. “I am so happy we kept the free dance music from last season because I had spent so many hours putting it together. This year I could just spend all my hours on the rhythm dance music and make sure everything was well done.”

“This is a transitional year with a lot of new feelings and a lot of new challenges, so it was natural to keep something familiar around — and then we ended up changing the whole program. But that is another story,” Sørensen added with a laugh. “We had to change it for the new rules, adding more features to the lifts and new elements so it has been a very exciting process doing that.”

Sørensen said his partner has “the musical DNA. It runs in her family. Her father plays in the Montréal Symphony Orchestra and her stepfather was a well-known DJ in Montréal. They both went to the Conservatoire de musique du Québec à Montréal — so, musicians everywhere.”

“When I was younger my stepfather decided to start cutting my music and then at one point he showed me how to use the program and I started cutting my own,” Fournier-Beaudry explained. “So both my dad and my step-dad helped me.”

Sørensen is now a permanent resident of Canada and is hoping to have his citizenship by August 2020. He has mastered the French language without taking courses or studying and his partner said his French is as fluent as his English.

“In Denmark, English is widely spoken and even before I moved here I think I spoke good English,” Sørensen said. “I am naturally good at learning languages without having to really study a lot. Laurence has never seen me study or open a French book. It just came together over the last 10 years.”

The goal now is to earn a place on the national team at the Canadian Championships in January. As their last competition representing Denmark was 2018 Europeans they will be eligible for selection for the Four Continents and World teams in 2019.

(Originally published in the IFS October 2018 issue)

RELATED CONTENT:

2019 CANADIAN NATIONALS

2019 SKATE CANADA CHALLENGE