There is no question that people of color are, and have always been, under-represented in the sport of figure skating. Over the past three decades, there have only been a handful of prominent skaters of color whose names figure skating fans would quickly recognize: Debi Thomas of the U.S. who won the 1986 World title and Olympic bronze in 1988; Surya Bonaly of France, who reigned as European champion from 1991-1995; five-time World pairs champion Robin Szolkowy, who represented Germany from 2003 to 2014, and Florent Amodio of France, the 2011 European champion.

The current movement for more diversity and the eradication of racism in the sport hit a new plateau in May, driven by certain events in the U.S. that reverberated around the world, particularly in Canada and Australia, both of which also have indigenous populations.

In January — and again in the spring — of 2020 former Canadian ice dancer Asher Hill spoke out about his own experience with racism in his workplace, claiming he had suffered discrimination from another coach at the rink where he coached. Hill took issue with the governing body, Skate Canada, for not supporting him and properly investigating his complaints.

In Hill’s case, Skate Canada allowed the rink Hill filed the complaint against to choose its own third-party investigator instead of hiring one itself. Skate Canada accepted the report of that third-party investigator — apparently without question — which concluded the events Hill complained about never happened. Skate Canada subsequently dismissed Hill′s complaint — and then reprimanded him for instituting it.

That did not sit well with Hill′s national compatriot, Elladj Baldé, who felt driven to speak out in support of his friend, despite the possible consequences with respect to his work with Skate Canada. “You know, I have seen what systemic racism is like first hand through my father’s life,” he said. “In figure skating, you don’t necessarily ‘see’ it. First, it is an extremely subjective sport and it is almost impossible to know if certain decisions are based on race. It could be choreography; it could be your costume —the reason why certain things were not given to you. So it is very hard to quantify whether things were racially based.

“I never truly saw that as too much of an issue, but what I did see, especially with Asher Hill’s story, was what looked like a direct example of systemic oppression. Someone experiencing forms of racial discrimination and coming forward about it, and then not only having them dismissed but also being reprimanded for it. I saw that as extremely problematic. I do not know the details of the story but I know what I experienced — I know what my dad has experienced being in the black community and I knew I needed to stand with that.

“If Asher’s voice was not going to be heard in the skating community then maybe my voice would help. So I decided to go forward with it. I knew that this could have an impact with Skate Canada but at that point for me it didn’t matter. It was a fight that has been ingrained in society for centuries and while my personal connection to this experience is not on the same level as the masses that have experienced discrimination and oppression, it should never be happening to anyone.”

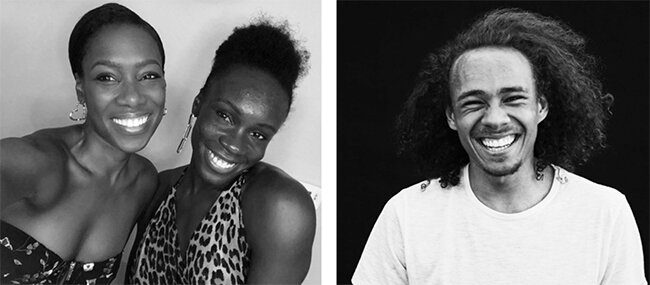

Following the murder of George Floyd, Baldé, Mariyah Gerber, a professional figure skater, and American coach Michelle Hong started the Diversity and Inclusion Alliance, a movement that aims to make figure skating a more diverse and inclusive sport. The goal is to find resources not just for black and brown communities, but also for other under-represented minorities to encourage and enable them to get into sports such as figure skating.

Two French skaters — Vanessa James, the 2019 European pairs champion and Maé-Bérénice Méité, a six time national champion — joined the alliance as soon as it was formed, and came armed with a definite mindset to make the sport more diversified and inclusive.

“At first, we had to identify all the problems we wanted to solve and that takes some time,” Méité said. “Then we have to set guidelines and decide on the action we want to take with all federations, but mostly in Canada and the U.S. right now. We have so many ideas and so many people. It is also about bringing awareness to the sport. Some people don’t know and would not even think about figure skating. Maybe it is something they don’t do usually or because of their environment they are not introduced to the sport. I think awareness is something we can work on.”

“The problem with people participating in some sports can be a financial one,” said James. “Some communities cannot afford to be in a sport like figure skating, equestrian or fencing because they are all expensive sports. That’s where you start to see the gap. It is not based on talent or ability, but on what a family can afford.

“Raising awareness and developing resources and funding to assist certain minorities and kids with talent — that is what is needed. People that are very talented and motivated need clubs and federations to help them, to push them forward to be outstanding in their chosen sport.”

James said employing scouts to identify talented children and supporting them with scholarships would be a good place to start. “There are companies that are giving hundreds of millions of dollars to minorities and black communities, maybe one could start a foundation for minorities in sports.”

She also noted that the Diversity and Inclusion Alliance has received positive feedback from both Skate Canada and U.S. Figure Skating. “The USFS sent out an email stating it was going to put together a group to help, support, discover and increase diversity in the sport. So that is a big step … for U.S. Figure Skating to actually have a body of people trying to make an impact in this area is very nice to hear, especially within just a short time after the start of this movement.”

Méité agreed. “We will start seeing some changes soon, because already the federations are starting to be a little bit more responsive. Elladj, Asher and Michelle have already received some feedback from Skate Canada. Asher’s sister started the first black owned figure skating school in Canada and we want to promote that, too. Things are looking to move in a better direction.”

James and Méité are also supporting “DiversifyIce,” a movement founded by Joel Savary who is partnering with former U.S. competitor Elliot Halverson. Savary has penned a book “Why Black and Brown Kids Don’t Ice Skate,” in which he outlines many of the issues he sees as problematic with the sport.

“Things have been happening very quickly,” James said. “Just imagine in the next few months and years the difference that we could see in figure skating and many other sports. Hopefully it will not be just figure skating. We want it to be diverse and inclusive. It’s not just about black people and minorities. We want all people that may not be able to afford figure skating lessons, no matter what color, to be supported if their mission is to be the best, and they have the talent and the work ethic to do so. It’s very unfortunate that many talented kids cannot afford to follow their dreams. Whether it is race, gender, sexuality or disability we need to make sure that everyone is included and has the same opportunities to get to the highest level.”

Unlike many others, James, Méité and Baldé feel fortunate not to have personally experienced racism in the sport. “When I first started skating, I didn’t really think about color,” said James, whose skating career began in the U.S. “I grew up in Bermuda where there are many different ethnicities, and for me it was normal to have a lot of fair skinned friends. Going into skating it wasn’t strange for me to be the only black person. No one ever said anything about it, so it wasn’t obvious to me. I was completely comfortable.

“My parents would say, ‘you won’t see many people like you in the sport, so you always have to work harder and try to be the best because you may not given the benefit of the doubt — just because they don’t see people like you often.’ I only realized as I grew up that yes, definitely, I was the only skater of color. But it was only because people started asking me things like, ‘How do you feel being the only black skater?’

“When I won British nationals as a single skater, a newspaper wrote: ‘Vanessa James, the first black British national champion.’ That made me uncomfortable because it’s not something that I really thought about. It should have been, ‘Vanessa James, British national champion’ and not the ‘first black.’ It shouldn’t matter what the color of your skin is. What made me most uncomfortable was not being the first black champion but the fact that people chose the color of my skin as something to report.

“When I was young my role models were actually Michelle Kwan and Tara Lipinski. They are the two that really got me into figure skating and they are two great role models still to this day because of the people they have become and how they conduct themselves. Michelle Kwan is very outspoken about black lives matter and Asian figure skaters.”

Méité has had a similar experience. “Where I grew up we had white people, black people — people of all color and many ethnicities at my skating club. I think in France we don’t really have a problem with diversity because when you look at our team — there are people from everywhere. It was never a problem at all for me. I was just there to skate and people saw me as a figure skater and not as a black woman on the ice.”

Growing up, Méité looked up to Bonaly — who she believes paved the way for herself and others — but also to Kurt Browning, Brian Joubert and Philippe Candeloro. ”It didn’t matter to me if they were black, white, or whatever,” Méité said. “I just saw them as skaters and I loved them.”

However, Méité does know that Bonaly faced racial discrimination during her career. Though they have never discussed it, Méité said “because she went through all that she surely opened many doors for us.”

James believes that Bonaly did not talk about her negative experiences so as not to discourage young skaters of color getting into the sport. “As a child, my parents did not talk to me about the racism I could face. I think children need to be protected from that. It shouldn’t be a burden and kids shouldn’t be afraid of the color of their skin. That should be talked about at an older age.”

James, who competed domestically in the U.S. and internationally for Great Britain and France, has a wide range of experience to draw on. When starting out as a young skater in Washington D.C. there were a few black skaters at the time that she looked up to such as Ramata Sow, Brittany Adams and Derrick Delmore. In Great Britain, she was the only black skater at a high level, but the situation was completely different when she went to France where there was Yannick Bonheur, Yretha Silete, Amodio, Chafik Besseghier and Méité.

“That was the most diversity I had ever seen at a high level in figure skating,” James said. “That’s where you really see the difference. I feel like because we are so multi-racial, it’s a beautiful team. No one person looks like another person and we all love each other, black, white, brown or mixed. It’s really nice to see and I think it does help younger generations to see that it’s possible.

“But, I feel that I am lucky to have never really had bad experiences, no matter what country I was in. I think the skating community is a very loving community and I have to say that I’m very lucky never to have experienced such hardships.”

James and Méité both said they felt very welcomed and accepted when competing in countries such as Russia or Belarus, despite initially not knowing what to expect given there are not many colored people in those nations. “When I did my first Grand Prix in Russia, the love I felt from the crowd was one of the best ever. It made me fall in love with Russia actually,” Méité recalled.

However, both revealed they have seen occasional racist or negative comments posted about them on the Internet. “When I go on YouTube I sometimes see rare comments like, ‘why is this girl on the ice,’ ‘black isn’t beautiful on the ice,’ ‘black people shouldn’t be on the ice’ — things like that,” James explained. “But it is rare compared to the thousands of positive comments. If someone takes the time to write such a negative thing, you have to wonder how miserable their lives must be to take the time to write something so hateful about someone you don’t even know. You can have your opinion, but for me it also comes down to a lack of education, lack of culture, and a lack of experience.”

Méité said she has only had one experience like this. “Someone made a comment about a picture of me saying that I look like a monkey and that I shouldn’t be on the ice. I was kind of young when I saw that — around age 15. It did hurt me because I am aware of my body and know I am a little bigger than others. I knew that but that comment didn’t help. It taught me not to read comments anymore. I read the good comments, and the bad ones I just erase without ever taking the time to read them. I don’t take the time to reply either because that’s a waste of time. We tend to focus on the bad — when we have like 99 good comments and one bad we only remember the bad one. You have to learn how to filter all those bad things.”

James and Méité said overall they feel safe living in Florida and both have had different experiences than those of so many other colored people in the U.S. But, Méité does admit to being scared sometimes when she is driving alone.

“First of all, we are in good communities that have the resources, that have the money, that have education. There are poor areas in the U.S. but we’re lucky enough not to be in those,” James explained. “It shouldn’t matter where you are. It is scary that you could be racially profiled and considered a criminal just because you are black and you are in a poor community.”

Méité, however, has encountered another type of discrimination with respect to her height and build because she is not typical of the stereotype figure skater. “It is not the norm that people are used to seeing on the ice,” the reigning French champion said. “I am very athletic and at times that seems to be a problem for some people who pass judgment before I even step onto the ice. They think I can only jump and I cannot be artistic. Sometimes I just feel like I can’t make any mistakes.”

Baldé and Hill were the two lone soldiers of color on Canada’s international figure skating teams throughout their respective careers. “I was never able to look up to someone who looked like me,” Baldé said. “There is a reason why there are so few colored people in the skating community — there is a huge lack of representation. I have heard people argue that if kids had the choice they would pick another sport like basketball or football. But what is the reason for that? It is not like they do not want to skate or think that skating is not a beautiful sport, but as a young kid you identify with someone who looks like you.

“So, obviously if a young kid is watching a figure skating competition and there are not many skaters of color, there is much less chance of that kid being inspired and saying, ‘Oh yeah, this something I want to do and be successful at.’ Unlike basketball, where there are 10 to 15 players that look like the kid and who are extremely successful. The kid looks at that and says, ‘I see myself in these people or that specific player. I can do that as well.’ That is one big reason why the skating world is so under-represented.

“My father, one of the most intellectual men I know, studied in the Soviet Union, which at the time was one of the strongest academic powerhouses in the world. He finished his studies then and then went to Canada where he was not able to find a job in his field and had to drive trucks for a living. People told him he would not get a job in his field because he was an immigrant and because he was African. ‘They are not going to prioritize you.’

“Skating is very expensive so a lot of parents that are brought up in those systems can’t afford it, and that is why we don’t see a lot of skaters of color. I want to change that. I want to be part of a group that is going to work actively on a daily basis to change that and bring in the next generation of color and other minorities. There are so many other minorities you do not see in figure skating for so many reasons.

“I feel that the weight is on me to try and make a change for the black and brown community in figure skating because it is a tight circle and you have fit a certain box to make it in the sport. We all know how sometimes old fashioned and behind the times it can be in certain ways, and I hope that in some way I can help inspire.

Baldé said the alliance has formed a committee and has now evolved into a big team with connections all over the world. “We are working on lots of projects right now to help change the system and also help change the skating culture, which is rooted in elitist white European men. Even different genders and races are not fully accepted in this sport so we have to change the culture.”

UPDATES:

Méité recently underwent physical therapy for her left knee but hopes to be back on the ice training soon and is looking forward to the new season. “I am keeping the programs secret right now, so all I will say is that Adam Rippon will be doing my short program and it is going to be passionate and profound. For the free skate, which will be entertaining, I will be working with an off-ice dance teacher — and obviously with my coaches John (Zimmerman) and Silvia (Fontana).”

James is currently coaching part time at her training rink. Her future is still undecided, but she hopes to resume training in the coming weeks.

Both skaters will first need to take a cardiovascular test as required by the French federation. Due to the fact that Florida has been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic they have not yet been able to attend at a hospital to take the test.

Baldé has been in high demand on the international show circuit since his retirement in 2018. He is looking forward to returning to touring and performing as soon as conditions permit. You can read our in-depth interview with Baldé in the October 2020 issue of International Figure Skating.