Every now and then she will notice someone on a hospital ward giving her a certain look. A lingering glance from someone who wonders if she is perhaps not just another typical student from McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine in Montréal. They know they have seen her face somewhere though they cannot place it right away. Eventually, the penny drops.

Almost a decade has passed since that heart-breaking week at the 2010 Olympic Winter Games, when Rochette lost her beloved mother, Thérèse, to a heart attack. Somehow, she summoned the courage to produce the defining moment of her career — and as the world held its collective breath she skated to a bronze medal in Vancouver. As it turned out, Rochette never competed again, moving on to a life of show skating and other off-ice pursuits such as skydiving.

In 2015, she entered McGill University, fulfilling a life-long desire to study medicine. She now spends most of her days on hospital wards, clad in a plain white coat. Less than a year from now, she will be addressed as Dr. Rochette — a thought that evoked a burst of laughter when this reality was presented to her.

Now in her final year, Rochette submitted her application for the residency program in November and said “interviews take place in January and February and we get our answer in March.” McGill students are permitted to do an internship at a different university hospital in their graduating year and Rochette is now fulfilling that requirement at a local hospital in Montréal.

While some of her fellow students applied Canada-wide for a residency position, Rochette hopes to stay in Montréal, or at least as close as Ottawa, Toronto or Québec City. “As a resident doctor at a hospital I won’t be able to prescribe anything and will be supervised for the next two to five years. Everything I do will need to be approved by my supervising doctor,” said Rochette, adding that she is scheduled to write her licensing exam in May.

She has not yet decided in which area of medicine she would like to practice, but there are already many options to consider — and perhaps more to come. “I’ve done all my core rotations: surgery, internal medicine, cardiology, family medicine and psychiatry, so I have an idea,” the 33-year-old said. “But it’s interesting. Sometimes you think you have an idea about what you want to do and you think you’re going to love it — and then you realize you really don’t like it. It is true with the opposite, too. Some people go into med school really wanting to do surgery, but after their surgery rotation, it’s ‘nope, not for me.’ And then they want to go into internal medicine.”

Rochette had to do a surgical rotation last year. She described it as one of the most intense in terms of not having much free time away from the hospital. The condominium she has owned in Old Montréal the last eight years served as a respite for sleep, a few quiet moments with her cat Leo, and not much else during those rotations. “In surgery, you start at 5:45 in the morning, and you’re there until 7 or 8 p.m. I would eat a sandwich in my car on the way home, take a shower and go to bed,” she recalled. “You don’t have a life. You don’t see the sun for two months in the winter. I have a lot of respect for people who do that for a living because it’s not easy. I don’t want to do anything surgical.”

She also experienced a different side of medicine in early 2019, when she spent a month in Puvirnituq, a remote Inuit community in northern Québec. “It was part of my family medicine rural rotation. I thought it would be a really cool experience because we don’t know much about those communities up north,” Rochette explained. “Just to be there working and see how people live was very interesting. It was an eye opener.”

One might think that cardiology would hold a particular interest for Rochette, given that heart disease was the underlying cause of her mother’s premature death. However, the road to practicing in that field takes many more years and while Rochette said she loves cardiology she wants to start practicing medicine. “I think I would have loved cardiology anyways because as an athlete it’s pretty cool to understand how the heart works, especially after what happened to my mother, and also my grandfather and my uncle … there’s a lot of heart disease in my family,.

“Also, through my work with the Heart and Stroke Foundation and the Heart Institute in Montréal, it’s something that I really got close to. But I don’t know if that will be my choice of career because with cardiology, it’s six to eight years of residency. I’m 33 now, so I would not be done until I am 40 or 42 years old. That will also influence my decision for sure.”

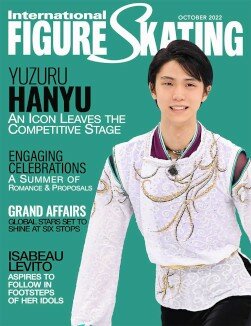

NEW ERA APPROVAL

Rochette finds it easy to understand why fellow Canadian Kaetlyn Osmond, in the wake of winning a World title and two Olympic medals (ladies and team) in 2018, would walk away from the competitive side of skating at age 24 and glide into the touring life. “She accomplished everything she wanted to and even more. She won Worlds, she got her Olympic medal, so yes, I can definitely understand that,” said Rochette. “With skating, you need to have a very strong discipline every year to compete and it’s not easy. When you have the opportunity to do shows, you get the best of both worlds. You can do what you love and make money without the stress of competition. Kaetlyn loves performing so it’s great for her to skate freely without that stress.”

The Montréal native is thrilled the World Championships are coming to her hometown in March. She and Patrick Chan are the athlete ambassadors for this competition, and Rochette believes it will be “great for the city and, hopefully, for skaters and skating fans to discover Montréal.” She will also be the athlete ambassador at the 2020 Canadian Championships in January.

She is also looking forward to being one of those fans who will have the opportunity to see a new generation of skaters with whom she is thoroughly impressed. “I love to watch and I love to see how it’s evolving, and seeing these younger skaters doing quadruple jumps … I think it’s crazy, and I’m glad I’m not competing during this time. I feel like they’re so good,” she said. “It’s interesting to see how every year the rules are changing a little bit, and how the skaters are using those changes to their advantage. It’s exciting to see all the guys doing these quad jumps that we never thought would be possible.

“There’s always people complaining about the technical side taking over too much, but you can’t be afraid of progress. It’s very exciting to see the evolution, but it’s also important to keep the artistic side — it’s what makes figure skating, figure skating.”

THEN AND NOW

Though becoming a doctor will fulfill a lifelong dream, Rochette admits a part of her still misses life on the ice. Skating brought her notoriety and public acclaim — in addition to her Olympic success, she claimed six Canadian titles and a World silver medal — along with memories that will stay with her for a lifetime.

Rochette’s competitive life ended in Vancouver in 2010, but she said it was not supposed to wind up that way. She had visions of perhaps competing for another year or two, maybe even going to a third Olympics in 2014. But life changed in so many ways after those Games, both on and off the ice, that those plans were shelved. Today, she admits to a tinge of regret about how it ended. “I didn’t plan on stopping right away after Vancouver — I wanted to do one or two more seasons, maybe get a World title,” she recalled. “But the way things happened after Vancouver — there was my mother’s funeral and I didn’t go to Worlds. I started training again at one point for the Japan Open, and I wanted to do the Olympics again. But, then I started doing shows, and there were so many great opportunities I never had before that I wanted to take — even some things outside of skating. So I never went back to competing.

“The first few years … the first cycle was hard. I was still skating in shows, but I really wanted to be in the Olympics again. When I was at the Sochi Games in 2014 (as a television commentator), it was bittersweet. Nothing beats being at the Olympics. But you have to be careful. You need to find something else that will … maybe not replace it but will give you the same thrill in life and motivation or satisfaction. Nothing will ever beat my life as a skater. It was amazing. We travelled the world, we had a great skating family, and there are people I still keep in touch with. Skating gives you that big family and gives you friends on almost every continent. That’s very cool.

“I don’t have any regrets, but at the same time, I miss it. I miss seeing the world, or being in a hotel in Japan and going to different restaurants. Show life was much more low stress than competition and we had so much fun together as a group. But then, it’s not something you can do until you’re 50 — well, don’t tell Kurt Browning I just said that — but it’s rare, and I feel like not many girls are doing it. I did Tessa and Scott’s show (the ‘Thank You Canada Tour’) in Québec City … it was cool to be back on the ice,and I got to do some of the group numbers. I do miss the crowds and I do miss skating, but it’s time to do something else. I feel like I’m so far away from skating nowadays that when I watch it, it’s exciting and I’m happy to just be watching it.”

When asked if people in her new world of medicine know her history as an Olympic figure skater, Rochette laughed. “Sometimes, a nurse will be looking at me funny and ask, ‘Were you here last year?’ or ‘Did we do a rotation together?’ Then I’ll come back the next day and the person will say, ‘Oh, I know who you are now.’ It happens a bit, but not as much as after 2010. It’s different now.”

Nonetheless, all these years later, Rochette still finds it difficult to explain the rollercoaster of emotions in Vancouver and how she handled it. To many, she will always be remembered for what transpired in February 2010. It is something she now understands was inevitable and she is content with that legacy.

By the time 2020 Worlds roll around, it will have been a full decade since the week that forever changed her life. Rochette ponders that thought, and while so much time has passed, there are momentary encounters that bring it all back. “I still sometimes meet people in the street who offer their condolences about my mother because they’ve never met me before,” she said. “But it’s been nine years and when I remind them, they say, ‘Oh, really, it’s been that long?’

“I can’t really change that. People remember and I think a lot of people were also living some of their hardest times through my story. A lot of people have come up to me and said things like, ‘Oh, when I watched you, I remembered when I lost my father.’ Or things like, ‘I was going through a hard time’ or ‘I was going through cancer.’ I feel like a lot of people identified with my story and related it to what they were going through. I guess I didn’t realize that in Vancouver, but when I came back the next year, that’s when I realized the Olympics are a really powerful media. Sport is great but when there is a story attached to it … I felt a lot of support and I felt lucky to be in Canada.

“There were times after Vancouver that I thought I would never get over it. Time really does heal and things do get better, but you never completely forget. I still miss my Mom and I think about her every single day. Every time I have life choices to make, I think about what she would say. You just don’t forget that. I’ve given a lot of speeches across the country with the Heart and Stroke Foundation, talking about it so I don’t get very emotional anymore. I almost feel like someone else went through it, not me. I don’t know how to explain that. But, sometimes images stick with us. I look at my life now, being in school, and I do feel like it’s been a long time.”

Rochette said that the sporting world and the one she lives in now “are very different” in many ways. “Skating is a lot of muscle memory and sometimes my legs would be burning and my body would be tired, but my brain would not be as tired. But, with medicine you’re training your brain … I feel like the learning is very different. It’s more exhausting; I don’t know how to explain it, but sometimes you feel brain exhaustion. Sometimes, you see patients with different pathologies that you have no idea about, and that’s quite stressful. You have to learn very quickly on the spot. You might be quizzed by the staff and you don’t want to look dumb. So you’re always on your guard. That kind of stress level, at the end of the day — you feel it. Some days are better than others, for sure. And some days, the amount of stuff you learn during the day is overwhelming.”

It has been quite the journey for Rochette who cannot wait to reach the finish line and move into her new life as a medical practitioner. “It feels so great to study medicine and to learn about the human body,” she said. “I feel very privileged.”

RELATED CONTENT:

2020 CANADIAN CHAMPIONSHIPS