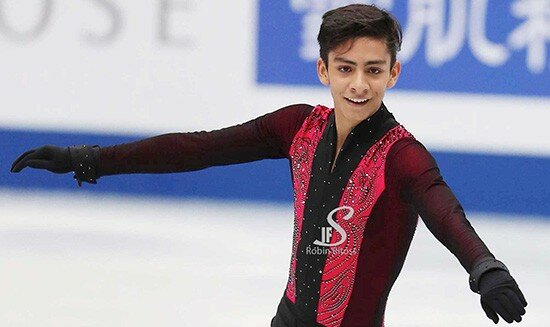

A dynamic young skater from Mexico is blazing a new trail for his country — one he hopes will be the starting point for future generations to follow. With his engaging style and dashing good looks, Donovan Carrillo has been charming audiences around the world the past couple of seasons. A natural entertainer, he believes figure skating has given him the perfect platform to express himself.

Born in Zapopan in the state of Jalisco, Carrillo is the son of two physical education teachers who encouraged their children to participate in sports at an early age. Carrillo tried karate, diving, gymnastics and soccer, but none of them grabbed his attention. Carrillo first became interested in figure skating when his older sister, Daphne, asked her parents if she could take lessons after watching a movie. He recalled watching her practice with her friends at the ice rink and began imitating what they did at home.

“I imagined that I was a figure skater,” said Carrillo. “I used to listen to music with my mom, and I would create programs with jumps and choreography in front of the mirror. As I got older I participated in school talent shows and I loved to perform. I loved having the crowd around me, supporting me, so figure skating totally fits into this part of my personality.”

Though his sister’s request would be the catalyst for Carrillo’s career path, it was a love interest that first got him onto the ice. “There was a girl who skated that I fell in love with, and so I asked my parents for lessons,” he recalled. “She became my girlfriend, but quit skating after about three months. I continued because I discovered that I loved to skate. It was an escape from school and everything, and I became very passionate about it. So I quit everything else and just focused on skating.”

In 2008, at age 8, Carrillo started taking lessons from Gregorio Núñez in Guadalajara. When that rink closed in 2013, he moved to León, Guanajuato — a city known as “the shoe capital of the world” — to continue training with Núñez. He started taking ballet and jazz dance classes to complement his training and his coach helped him with the choreography and performance aspects of his programs.

Carrillo made his international debut in 2013 at the Junior Grand Prix in Mexico City, where he placed 15th. He has been making steady progress every season and though he is still far from reaching an international podium, he has become the groundbreaker for Mexican figure skaters. His 22nd place finish at the 2018 World Championships was the highest ever achieved by a Mexican man.

His preparation for this past season hit a roadblock when he suffered an ankle injury last summer that took months to fully heal.“I was training in a rink where the ice was melting and I was tired. I went into a triple Lutz but I couldn’t rotate on my toe pick, so my body rotated but my toe pick did not because the ice was so soft,” he explained. “I popped the jump and fell on the ice. I was in a lot of pain. I couldn’t even skate — it was horrible.”

Weeks later, he returned to training despite still feeling pain in his ankle. He headed to Bratislava, Slovakia, for his first Junior Grand Prix assignment in late August 2018, where he finished 11th. “At the end of the day, I was able to finish the competition, but when I came home I sprained my ankle again because it hadn’t healed completely. So I had to stop skating for a while,” he recalled.

The injury forced him to miss his second Junior Grand Prix event in Linz, Austria. Carrillo hoped the break from skating would allow his ankle to fully heal, but when he returned to the ice in September he was still experiencing pain.

Carrillo finally returned to international competition in February at the 2019 Four Continents Championships in Anaheim, California. Carrillo and his coach had set a goal for him to land a triple Axel in the short program, and Carrillo was thrilled to not only achieve that, but to also earn a personal best score. His free skate, however, did not go as well as he had hoped and he finished in 17th place overall.

“I loved the experience because there was a lot of support. Even though my program wasn’t the best, people were cheering for me,” Carrillo said. “It was not the program that I wanted to give them, but they supported me even with the mistakes. It gave me the energy that I needed to keep pushing and fighting in the program.”

The 19-year-old started learning two quads last summer — the toe loop and Salchow — but was forced to stop practicing them when he suffered the ankle injury. He started training them again two weeks before Four Continents and hopes to include them, along with a second triple Axel, in his long program next season.

Carrillo opted not to compete at the World Junior Championships in early March — the last one for which he was age-eligible — to focus on the senior Championships. “Last year I did junior and senior Worlds and it was really hard because the programs were different. I couldn’t focus on both so I just practiced the senior free skate,” he explained. “I didn’t have a very good program at Junior Worlds, so we decided to focus only on seniors this season.”

He failed to make the cut for the free skate in Saitama, later explaining he had re-aggravated the ankle injury after Four Continents, and was unable to train at full capacity in the weeks leading up to Worlds.

With only a few Olympic-sized ice surfaces in Mexico, Carrillo trains at a rink in a shopping mall in León, and often has to do run-throughs of his programs during public skating sessions. He said that while “it is hard, it is not impossible. There is no other way. I know that it is not the best way, but if you focus on what you have to do, it doesn’t matter the circumstances you have. “It’s more the hunger that I have to be better than the adversities that I have to overcome. I just focus on doing my best. I try not to think about the bad things and focus on what I have to do—and what I have to do is train.

“The hardest part is that in a public session they have to play music. So, I have to do my programs with the music of the public session competing with my music … it’s difficult. Sometimes I can skate with no other people on the ice in the morning, but most of the time I have to figure out how to do my jumps and spins without putting someone else in danger.”

Despite his training conditions, when Carrillo competes he exudes a charm and presentation style — along with his infectious smile — that makes it easy for audiences to fall in love with him. “I want to give the audience the feeling that I have when I am skating. I want to share what I have inside with them,” he said. “I really like when people say things like, ‘You look like you are not stressed and are enjoying the competition.’ That’s what I want the audience to feel when I am skating. Even if the performance is not my best, that there is a positive energy in my programs.”

He draws inspiration from seven-time European and two-time World champion Javier Fernández who also came from a country where figure skating is not a priority. “Now people in Spain know the sport because of him, and I have grown up admiring him.”

Carrillo inadvertently brought attention to the sport in his homeland at a Junior Grand Prix event in 2016 in Yokohama, Japan. His program that season, “Hasta Que Te Conocí,” was a piece by Mexican composer Juan Gabriel, who passed away four days before the competition. “His death was big news in Mexico. People found out about me skating to his music, and TV networks started asking me for interviews. The ISU video of my long program received 1.7 million views,” Carrillo recalled.

“When I first started skating my friends knew nothing about the sport but watching videos of me compete has helped them to understand it better. Now with all the coverage online, they know who Yuzuru Hanyu and Javier Fernández are. It’s good because they are people who are not involved with the sport, but they know who the top skaters are.”

Over the years, Carrillo and Núñez have developed a partnership that both say is based on trust — and, according to Carrillo — generosity. “My coach supports me a lot. Since I started skating, he has never charged me for lessons,” he explained. “He wants me to be better every day. He tries to help me and is always pushing me to be better — not just in Mexico, but to be competitive on the world level. He believes in me. I trust what he teaches me every day, and I trust the plan that he has for me.”

Núñez, a former skater who has been coaching for 15 years, said it has taken a lot of work on both parts, “but Donovan learns quickly. I have other students, but Donovan is at the highest level.”

He attends coaching seminars in the U.S. and Canada to broaden his approach and also takes courses offered by the Professional Skaters Association. “At the PSA, they teach about the biomechanics and the technical side of the jumps,” Núñez explained. “We work with a coach from Canada who has helped me with all the doubts I have about teaching the jumps. I try to analyze the movements so that I can understand how to make the jumps better. I am always trying to get more experience.”

Though Carrillo has not yet had the opportunity to compete on the senior Grand Prix circuit, he is hoping he will get an invitation in the near future. His ultimate goal is to earn a berth at the 2022 Olympic Winter Games in Beijing. “When I was little my dream was to compete in PyeongChang, but now my principal goal is to continue training to fight for2022.This is just the beginning, and with years of experience competing at the world level, I will be prepared for the Olympics.

“I love to compete and I love to put my flag in different countries. I want to give the next generation hope that with hard work they can also go to international competitions, even if they train in Mexico. It’s not impossible. Most people think that you have to move to another country to improve, but you have to believe in our sport in Mexico. I want to give that to the next generation.

“If they see me at internationals, Grand Prix events, World Championships and ultimately the 2022 Winter Olympics, they will see that it is possible. I want to give them that hope. Right now there are three senior men in Mexico, but they do not have the scores to compete at Four Continents or the World Championships so they only get to compete at nationals. It’s improving though, as there are more skaters coming up in the next generation. The sport is growing in Mexico.”

Carrillo opened a crowd funding campaign in February and now has a number of private supporters. That same month the Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (a division of the Mexican government that develops and implements policies to encourage people to participate in sports and physical activity) announced that Carrillo would be granted funding beginning in March.

“I feel like a father to live this experience with Donovan, and I thank God that he has been advancing and showing improving results for our country,” said Núñez. “It is complicated because unfortunately in Mexico, it is not a very common sport and is somewhat expensive. We are not a powerful presence in this sport, and we are not supported much by the government. But a lot of people in our country have approached us with help so that Donovan can continue to compete and be able to move forward.”

(This article was originally published in the IFS June 2019 issue)