On a bitterly cold night in February 1988, Tracy Wilson and Rob McCall became heroes in their Canadian homeland when they claimed bronze at the Olympic Winter Games.

Following the World Championships, the ice dance duo headed to the professional ranks for what they hoped would be a long and lucrative career. However, it was not to be. Less than four years later McCall died, and a heartbroken Wilson quietly quit the sport.

It was an unlikely partnership from the beginning. In 1981, Tracy Wilson, who grew up in Port Moody, British Columbia, and Halifax, Nova Scotia raised Rob McCall were both looking for new partners. Wilson was concerned about the height difference; she was just 3 inches shorter than McCall. But when the opportunity to try out with him arose, Wilson knew she had to explore it.

“I called Rob and asked him if he would like to try out and he said he’d love to,” Wilson recalled.“ I told him:‘ The only problem is I’m 5 foot 6,’ and he said, ‘Look, there’s a Russian skater who has platforms on the soles of his skates to make him look taller. I can do that.’ I thought to myself, ‘Here’s somebody who’s willing to try anything.’”

The duo teamed up, and less than a year later won the first of seven consecutive Canadian titles. Their journey to the top level of the sport took flight with a victory at Skate Canada in 1983. Wilson and McCall were the first Canadian ice dance team to ever claim the title. Rising steadily through the ranks, the duo captured their first World bronze medal in 1986.They would repeat that feat twice more in successive years.

Behind the scenes, life was not always easy. With no financial backing, Wilson had to work, squeezing in waitressing shifts whenever she could to make ends meet.“ The reality of what we had to do financially … was so tough,” she recalled. “When we went to our first Worlds, we borrowed outfits from another dance team in Halifax that Rob knew. Rob would bead them, and I had to use carpet tape to keep the back side down.”

Wilson and McCall won the hearts of a nation when they captured the bronze medal at the 1988 Olympic Winter Games, making history that night in Calgary as the first North American team to claim an Olympic medal in the ice dance discipline.

Although 27 years have passed, that memory still burns bright for Wilson. “Calgary was just a huge honor,” she said. “To have that kind of opportunity in your lifetime, and the timing of that opportunity … How many athletes get to be in an Olympics and be chasing a medal at home? I just felt so grateful for that. Winning the bronze medal was huge, and to feel like you’d left your indelible mark on the sport or whatever — there was a lot of power in that.”

THEN THERE WERE TWO

They were the three amigos, a trio of Canadian figure skating stars who were virtually inseparable as they chased their Olympic dreams. Now, more than 30 years later, the bond between Wilson, Brian Orser and McCall, who died in November 1991 at age 33 from AIDS-related brain cancer, remains strong. “I really do still feel Rob’s connection, and I try to keep that,” Wilson said wistfully over a late-morning breakfast in the Toronto Cricket Skating and Curling Club lounge as she recalled the special times she spent with McCall.

“We were so close, the three of us,” Wilson said. “We learned from each other, we pushed each other. I remember when I went to my first international competition, … I really connected with Brian.”

As Wilson watched McCall fading away, he did his best to ease the profound sadness of those who were about to lose him. “When he was diagnosed, it was just devastating,” Wilson recalled. “I don’t really know how to describe it other than that. But he was brilliant. I have to say he made it easy on people. His levity, his humor … he was unbelievable.”

McCall’s death, which hit Wilson hard, caused her to step away from the sport. After taking part in a tribute show for McCall in Toronto in 1992, Wilson did not set foot on the ice for the next five years.

“I felt like we’d achieved such a level together,” Wilson said. “To know Rob … he was such a personality to skate with, and he made skating fun. His love for skating was so great.

“So for me to go out on my own held no interest. I thought that would be it for me because my joy from skating came in all those great moments we had, and I just thought it was time to move on. I really think a lot of it, though, in retrospect, was that being on the ice without him would have meant that I had to deal with losing him. My son Shane was born right before Rob passed away, and I just found it easier to get busy in my life and not deal with it.”

The dam of pent-up emotions finally burst during a Scott Hamilton tribute show in 1997 in Portland, Maine, when the void in her life was laid bare before the audience one night. “They asked anybody who had skated with Scott to come out on to the ice,” Wilson said. “It was actually the same town where Rob had been diagnosed with AIDS. I stepped onto the ice in the spotlight, by myself, and, at that point, I made up for five years of not crying.”

NEW DIRECTION

Shortly after that event, the ice beckoned her once again, and this time Wilson heeded its call. “I think Shane was 5, and he wanted to play hockey so badly. We had an outdoor rink, and he kept pestering me to skate. So one day I got on the ice with him and my other son, Ryan,” she recalled. “I was out there skating, and I thought ‘Oh, my gosh, this feels so good.’ It was like this revelation. And then I thought: ‘Of course it does; it’s what you did your whole life.’ In that setting, just playing with my boys, I had a blast.”

Soon enough, her sons were into full-fledged minor hockey, and Wilson was coerced into working with Shane’s team as a skating coach. “My goal was to get them to love skating. I wanted them to love the movement. It was just about agility and fun and the joy of movement,” Wilson said of the sessions that became known as the “Tracy Skates.”

“What was interesting to me was that I brought my ice dance background to it — moving your back, your arms and all of that — but I soon realized that all those kids wanted to do was go fast. It was just about speed. So I had to come up with things that would keep their interest and their respect. We did twizzles, footwork and … all of that other stuff.”

The Tracy Skates evolved into coaching seminars for Skate Canada and drew invitations from coaches at various clubs to share “the formula of what I learned as a dance competitor and what I had learned about power,’” she said. “That sort of became the basis of what I do now.”

TELEVISION CALLS

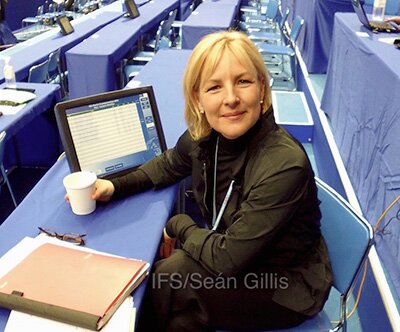

Wilson is perhaps better known to the younger generation of skating fans as a television commentator, a direction she had always felt her career would take after skating had run its course. Though her focus was not on becoming a figure skating analyst, Hamilton first got her on the air in that capacity for a U.S. network in 1990.

Wilson was also working with CTV in Canada, covering different sports. “The thinking was, if I started out as just a skating analyst, I’d get pigeonholed. So I did all the other sports for two years,” she recalled. She covered the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona as a CTV studio host, and upon her return home learned that she was pregnant with her second son.

“In Barcelona, I was stressed because I had an 18-month-old at the time,” she said. “I did enjoy that opportunity but not at the cost of family.” Wilson decided that focusing strictly on figure skating would be a better fit for her and her husband, Brad Kinsella, and their growing family. Throughout the years, she has used her position as a television commentator and analyst to educate and inform viewers about the sport and, in particular, the ice dance discipline.

“When I started in television, ice dance didn’t have much interest in the U.S., and it wasn’t covered much on U.S. TV,” she recalled. “I would begin my commentary with the differences between pairs and ice dance because the U.S. audience wasn’t that familiar with it.”

“When we went to Vancouver for the 2010 Olympics, there were three North American teams in contention. The NBC producer said to me, ‘When we cover the free dance, we’re going to come to you live in the warm-up, and we’re going to stay for the entire final flight.’

“That was such a tribute to ice dance, and it was such an honor to be a part of that.”

COMING FULL CIRCLE

Wilson’s connection with the Cricket Club began many years earlier, when she and McCall trained there for a brief period. It is also where, as an 18-year-old, she and Kinsella first met on a blind date in 1980. “We met in the parking lot at the club,” she recalled with a laugh.

In 2005, there was a crisis at the venerable club. All the coaches were fired, and the skaters subsequently fled in droves. Club management approached Wilson — and Orser, she later learned — to try to rebuild something from the rubble that had been left behind. “Brian had always been trying to get me back on the ice. He always tried to look for ways, but, until then, I just wasn’t interested,” Wilson recalled.

She and Orser initially agreed to work with the club as consultants for three months. “We had a lot of the same thoughts about what skating was to us and what we felt was important,” Wilson said. “We said to each other: ‘We’re starting from nothing, and it will become what it’s going to be.’ If we had picked up something that was already running, we would of had to go with it as it was. But, instead, we were asking,‘ What do we think? Who do we want?’

“People were just so happy to have somebody here, because they had nobody. Brian was still performing, and I had only been working with minor hockey players, but we started some classes, and it just started to grow. That was 10 years ago. It’s been really neat to be back together here.”

That early vision evolved into something that Wilson could never have imagined: the arrival of South Korean sensation Yuna Kim in 2006, who Wilson and Orser coached to the 2010 Olympic title, caused the club’s gates to open wide. Elite-level skaters from around the world began clamoring to train with the duo. Over the last decade, Wilson and Orser have become the go-to coaching team, guiding the careers of some of the world’s top skaters, which currently include Yuzuru Hanyu, Javier Fernández and Nam Nguyen.

“It’s really sort of funny that, here we are. I feel Rob has a lot to do with it. When we get too serious and then something funny happens, Brian and I will look at each other and say ‘Rob.’ That was the one thing he could do. He could bring out that humor in a real tense situation, and what a difference it would make.”

While Wilson finds joy in the smallest things, such as watching young skaters get their crosscuts just right, she also relishes the opportunity to build champions. “It’s such a privilege. We’re always looking for what each of them needs to complete their overall development. Every skater we work with is different,” she said. “What I’ve learned is that it’s give and take. I love the challenge because it keeps me sharp, and I am always pushing myself. My big thing is to move the sport forward.”

RELATED CONTENT:

JASON BROWN HEADS NORTH