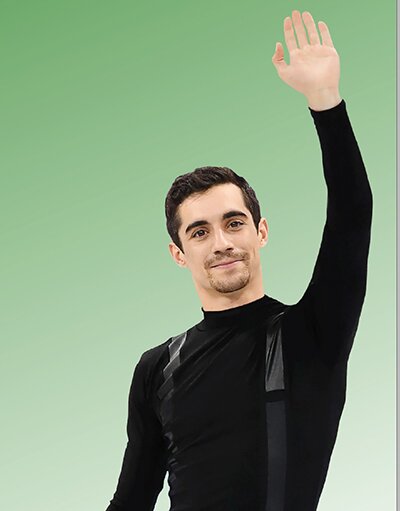

Spain’s Javier Fernández rewrote figure skating history many times during his 12-year career on the senior circuit. The first figure skater from his nation to win major international titles and an Olympic medal, he left the competitive arena in January as one of the most decorated skaters of his era.

Fernández closed out his career at the 2019 European Championships with a decisive victory, writing the last chapter of a career that, at its outset, he never imagined having.

Along the way, the 27-year-old from Madrid produced some impressive results, including being just the second man to break the 100-point barrier in the short program, the 200-point barrier in the long program and the 300-point barrier for the combined score.

Javier Fernández climbed to the top step of a competitive podium one last time in January at the 2019 European Championships in Minsk, Belarus, where the Spanish star celebrated a record seventh consecutive European title — a fitting end to his final outing. He now sits directly behind Austria’s Karl Schäfer, who claimed eight consecutive European crowns between 1929 and 1936.

Fernández, who had not competed since his bronze medal finish at the 2018 Olympic Winter Games, returned to the European Championships with the goal of writing the final historical chapter of his career.

After his highly successful show “Revolution on Ice” completed its run in Spain in late December, Fernández had returned to Canada to prepare for the Championships with his long-time coach Brian Orser. With just three weeks until Europeans, he and Orser opted to return to two pieces he had previously used — “Malagueña,” the short program he competed for two seasons (2015-2017), and “Man of La Mancha,” his 2018 Olympic long program.

Fernández said he had always liked these routines and thought they were particularly appropriate for his final competition “because they bring a little more Spanish to the ice.”

From the moment he arrived in Minsk, Fernández was the star of the show. At his first practice session, international fans cheered and waved Spanish flags. Everyone knew this would be the last opportunity to watch him compete and no one wanted to miss it. No matter what happened in Minsk, Fernández was adamant this would be his final competition.

Sitting in third after the short program, he took issue with a judging call on a quad Salchow but nonetheless remained optimistic. “I’m hoping to do really well and try to fight for a gold medal again. I’m known for comebacks, so if they let me, I’ll do it,” he said in reference to the reputation he first earned in 2013.

Fernández also had a trump card up his sleeve that his competitors did not have — a dozen years of experience competing on numerous major stages under intense pressure. And, as many of the competitors who skated before him in the long program stumbled and tumbled, Fernández rose to the occasion, winning the free skate and claiming the coveted title.

“You know, I’ve skated forever and done so many competitions and been in so many different environments that at some point you know what you have to do,” he said. “I was confident in myself. I trained great in a short period of time. It was efficient and I was sure I was going to do well.”

As he closed out this long and important chapter of his life, Fernández admitted to having mixed feelings. “I think it’s a bit sad because it has been 21 years of training and competitions. I’ve had a great career and I was able to accomplish much more than I thought I could. I wanted to win Europeans seven times in a row, but it was not my main goal. My main goal was to try to deliver a good performance to say goodbye to my competitive career.

“In the beginning, I felt a bit nervous but when the competition began, I started to feel more confident and comfortable. I was happy that I was able to skate well for the last time, but at the same time, sad because I know that I am not going to compete anymore. It was a good time but now the future is waiting for me. It is time to retire.”

EARLY DAYS

As a child growing up in a non-traditional skating nation, there was little indication that Fernández would ever become one of the top skaters in the world, nor did he imagine that one day he would spin to the top of international podiums, writing his nation’s skating history every step of the way.

Born in Madrid in April 1991, Fernández first took lessons at age 6, following his older sister Laura into the sport. Though he showed a natural talent from an early age he lacked discipline. Six years later he landed his first triple jump, but it was not until age 16 that he landed his first quad, a Salchow.

At that time, figure skating was considered a female sport in Spain, and growing up Fernández endured endless taunts from his peers. “People thought that skating and ballet were for girls,” he explained. “I was not thinking about skating at an elite level, or any level really. I was just skating as a hobby basically.”

In 2006, Fernández placed 23rd at his first junior Grand Prix in the Netherlands. He remembers the competition for one particular reason. “The skater before me had a terrible skate, and someone from my federation told me that my dad said, ‘Oh my God, if my kid does that, I will die.’ Well, I did exactly the same as him or even worse,” Fernández said with a laugh. “I was like draping everywhere, falling, stepping out. It was horrible. I got five or six deductions in the free program. That was very funny.”

At age 15, Fernández made his senior international debut at the 2007 European Championships where he finished 28th in the short program, failing to qualify for the free skate. His debut at the World Championships in Japan a month later — where he placed 35th — was an eye-opener, he recalled. “I was like: Where am I? When we went to practice, the arena was full. I was thinking … this is crazy. Everything was unbelievable. It was a great experience for me.”

Life changed in mid 2008, after he attended a summer camp run by Russian coach Nikolai Morozov. Fernández was unhappy because he felt he was not improving but was unsure what to do. “At the end of the camp, Nikolai said I was really talented and asked if I wanted to go to the U.S. and work with his team,” Fernández recalled. “I was shocked. When I joined his group that summer, I was not looking to be a great skater internationally. But when all these great skaters came, I was impressed.”

Two weeks later, Fernández moved to Hackensack, New Jersey. It was then that he first started to think he could possibly be successful. “But I still thought the people around me are so much better, and I am not going to be able to make it. Then as I started moving up the ranks, I said to myself that maybe I can do it, maybe it is possible.”

In 2009, he placed 11th at Europeans and 19th at the World Championships. His placement at Worlds qualified a berth for Spain at the 2010 Olympic Winter Games, the first since Daŕio Villalba earned one in 1956. Fernández finished 14th at the Games in Vancouver — the same placement Villalba had earned 54 years earlier.

With each season, Fernández continued to rise through the rankings, breaking into the top 10 at Worlds for the first time in 2011. That year, Morozov decided to return to his Russian homeland. It marked the beginning of a gypsy lifestyle, Fernández said. “We went to Moscow, Latvia and then to Italy. It was a great experience because I got to see different parts of the world.”

But a year later, he had grown tired of the constant upheaval. “It was really hard for me personally because I had no home. I did not know where my home was anymore. We went from one hotel to another and from one sports complex to another. You don’t have your own stuff; you don’t have your own life. That was hard for me. I got sick of it. I just wanted to live in one place.”

Disillusioned, he returned to Spain to figure out a new plan. It was decided he should go to Canada and train with Orser. “We knew he had a lot of good skaters and he was a great skater himself. So, I went to Toronto for a tryout to see how everything would work. I liked it from the very beginning and decided to stay.

“I got absolutely everything when I went to Toronto — two great coaches (Orser and Tracy Wilson) and the greatest choreographer (David Wilson).”

ON THE RISE

Fernández’ first international success came early in the 2011-2012 season, when he mined silver at both his Grand Prix events and qualified for the Grand Prix Final — the first man from Spain to ever accomplish this feat. His bronze medal finish at the Final in Québec City was another first for his nation. “Last year, I wasn’t even close to the podium. This year was a big surprise,” Fernández said at the time. “When I finished my short program, I was so surprised at how the audience reacted. I will never forget how crazy they went over it. That moment will stay with me forever.”

He closed out that season finishing sixth at Europeans and ninth at the World Championships.

Fernández continued his upward spiral in the 2012-2013 season, winning Skate Canada, his first Grand Prix title. “I thought I was going to cry on the podium. To see my flag in the middle of the three and to hear my anthem was something new for me,” he recalled of the first major victory of his career.

That season — and for the second year in a row — Fernández was the only European man to qualify for the senior Grand Prix Final. Fifth after the short, he won the free skate but landed in fourth overall.

The 2013 European Championships did not get off to a great start. His skates were lost at the airport and located only the day before the start of the competition. Unfazed, Fernández placed second in the short and went on to capture his first European title in a runaway victory. “When I stepped on the podium I was thinking, ‘This cannot be. This is impossible.’ It was crazy that I won the European title. To be the first skater from Spain … it doesn’t matter what happens in the future. Let’s say, I can die happy.”

At the World Championships a month later, he found himself buried in seventh place after the short program. The then 21-year-old was hardly in a position to expect a historic ending to his season. Skating 15th in the penultimate group in the free with nine skaters still to compete, he resigned himself to the fact that claiming a spot on the podium was out of his reach.

But as he sat backstage watching those nine competitors on a television monitor, Fernández saw his score continue to hold up until the end of the competition. “After Patrick Chan skated, he and I were sitting together, and I said to him: ‘Patrick, if I am third, I don’t know what I am going to do. I could just die here. I could have a heart attack.’

“After the final skater, I was like, ‘Oh my God. What just happened?’ It was like God just gave me a big opportunity,” Fernández added with a laugh. “I didn’t know what to do. Jump, cry, hug Patrick. I was so, so happy.”

Fernández claimed the bronze, the first medal of any color won by a Spanish skater at a World Championships.

The following season he failed to make the 2013 Grand Prix Final, but he saw it as a blessing in disguise. With Europeans and the Olympic Winter Games looming on the horizon, every moment of training and preparation counted.

After winning his second European title in January, expectations were high that he would capture a medal at the Games in Sochi. “It’s a whole new game,” Orser told Fernández at the time. “You have been to the Olympics before, but this is different. Last time, you went to get the uniform; this time you are a contender.”

Third after the short, that seemed to be a definite possibility. However, at the very end of his free skate, Fernández executed a second triple Salchow, which as a repeated jump received no points. Had he done a double Axel or a triple toe loop, the bronze medal would have been his. Instead, he settled for fourth. “It wasn’t my day; I was stumbling a lot. The only thing you can do is fight until the end, and that’s what I did.”

A month later, he captured his second bronze medal at the World Championships.

FINAL QUAD

Heading into that post-Olympic season, Fernández had initially planned to sit out the Grand Prix Series and focus on the 2015 European and World Championships. But when it was announced that Barcelona, Spain, had been selected as the venue for the 2014 Grand Prix Final, earning a berth at that event became his sole focus.

“I had no choice. I had to keep skating,” Fernández said. “It was hard to get back onto the ice at the beginning of the season because I knew what was coming. I was tired, but I also knew that I could not miss making the cut for the Final, no matter what. I did not know how I was going to do it, but I had to do it.”

When he returned to his Toronto training base after his summer break, Orser noticed a difference in his student. “There was a change of attitude, but I really did not know which way it was going to go,” Orser recalled. He soon realized Fernández was embracing the upcoming season like no other and “jumped into it with both feet.”

However, earning a berth to the Final was not a walk in the park. After landing in second at the Grand Prix in Canada, he needed a top finish at Rostelecom Cup to guarantee a spot in Barcelona. Fernández came through, winning the event in Moscow with 13.01 points to spare.

Though most elite skaters are seasoned veterans competing at home by the time they hit their late teens, the Final marked the first time Fernández would contest a senior international competition in his homeland. The pressure on his shoulders to skate well and win a medal was intense.

As he took his place on the biggest ice stage his nation had ever seen, Fernández found himself suffering from stage fright. In the short, he fell on the opening quad, barely landed a triple Axel, and placed second to last. It was not the performance he had hoped to deliver. “When I went out for my program I was really, really scared, and then I heard all the people screaming, and it was so loud. I did not know exactly what to do,” Fernández recalled. “It was a new experience for me — my first time competing in my home country. I wanted to do a great job, but I was afraid that I was going to do a bad performance. I was really nervous and I was really scared.”

Orser said there had been times when Fernández had not skated well and his attitude was, ‘I don’t care — whatever.’ “But this time, it was very positive, very mature.”

With nothing to lose — “I was fifth, so if I skated badly in the free, I would come sixth” — he turned in a strong long program performance and captured the silver medal. The Spanish fans went wild. “It was the best medal I have won at a Grand Prix Final, and it was even more special because I won it at home,” a relieved Fernández said.

A month later, Stockholm proved to be another lucky city. Though his performances were not perfect, his skating skills and interpretation were not lost on the judges. Fernández romped into first place, claiming his third consecutive European crown by a margin of almost 27 points. It was the first time in 26 years a man had claimed three straight European titles. (Russia’s Alexander Fadeev was the last man to achieve the feat in 1989).

At the 2015 World Championships in Shanghai, China, Fernández hit the highest note of his budding career. Heading into the competition, it was a given that the battle for gold would be between Fernández and his training mate, Yuzuru Hanyu. Though Hanyu sat in first after the short, his subpar free skate score was one Fernández could beat — and he did.

When the final results were posted, he was in disbelief. “I had no words. It was unbelievable,” he recalled. “This was not even in my dreams. I said to Brian, ‘How? What happened?’ This is impossible.”

As he stood atop the podium, Fernández was still trying to absorb his accomplishment, another first for Spain in any discipline at a World Championships. “Some people cry, but for me, every time I land on a podium, I just cannot believe it. My emotions disappear. I can’t explain it.”

When Barcelona was selected to host a second consecutive Grand Prix Final, Fernández found himself in the same position he had been in a year earlier — and earning a place at the 2015 Final once again became his number one priority. That season he won both Cup of China and Rostelecom Cup and ranked first heading into the competition.

Fernández claimed a second silver medal in Barcelona, earning a long program score that topped the 200-point mark for the first time in his career — only the second skater to ever achieve it.

In January 2016, Fernández claimed his fourth European title. It was symbolic that the event took place in an arena in Bratislava that was named in honor of Ondrej Nepela, the 1972 Olympic champion, who claimed his fourth of five European titles that same year.

“To get four European titles in a row is something really special, as my name now means a little bit more in the history of the sport,” Fernández said. “Not even Evgeni (Plushenko) had the chance to get four titles in a row. It’s something to be proud of because he is an amazing skater and a great hero of mine.”

When Fernández claimed his first World title in 2015, the global skating world cheered his historic achievement. But many in his Spanish homeland were not so enthusiastic about his accomplishment and some questioned his “luck” on that evening in Shanghai.

Heading into the 2016 World Championships in Boston, Hanyu was the man many expected to win following his record-breaking performances earlier in the season. But as Fernández had proven the year before, he should never be counted out.

Those Championships were a complicated and challenging time for the Spaniard. On the day off between the short and long programs, he began experiencing a sharp pain in the heel of his landing foot. “Every time I tried to bend, it hurt so much I could not do anything,” he said. “Brian told me to put some ice on it and we would see what would happen tomorrow.”

The following day, Orser took him to the medical room where doctors did an ultrasound, performed therapy and gave him stronger anti-inflammatories. They also gave him a protective pad for his heel so it would not touch his boot. “When I put my skates on and went out for the six-minute warm-up I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is amazing. I don’t feel any pain,’” Fernández recalled.

“That day, instead of focusing on the scores, I focused on what it would take to win. When the first person is 10 or 15 points ahead of you, that makes it hard and I was thinking to myself that being second is not all that bad. It was not an easy time for me.”

That night he sold his “Guys and Dolls” long program to the world. His portrayal of Nathan Detroit was so convincing that one could almost smell the booze and cigarettes as he wove his way through the challenging routine. In a repeat of what transpired a year earlier, Fernández not only came through when it really mattered — he claimed the title by a stunning 19.76-point margin. His performance earned 26 perfect 10.0s for program components. “I don’t know what happened, but I did like maybe the best program of my life. I was so afraid that I could not compete and then I did one of my best programs ever.”

Winning a second World crown brought Fernández more than just a medal and a title — it also brought him a level of respect in his homeland that had been absent the year before. “So many people thought that I got lucky when I won my first title. I heard that so many times,” Fernández said.

His victory made front-page news in space usually reserved for tennis or soccer heroes in his Spanish homeland. Royalty and the highest levels of government feted him, but the accolades and respect from his countrymen had not come easily. “In interviews in Spain, after I won my second title, people were like, ‘Oh, when you won the second title, I realized it was not luck — you were good.’ That was the idea that so many people had in Spain, but I guess they realized when I won the first time it was not because I was lucky,” Fernández recalled.

Two weeks later, the then Prime Minister of Spain presented him with the Gold Medal of the Royal Order of Sport Merit, the nation’s highest honor. A few days later, he attended at Madrid’s Zarzuela Palace, where he met with King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia of Spain.

Fernández easily won both his Grand Prix assignments in France and Russia the following season. However, the Grand Prix Final in Marseille did not go well and he finished off the podium in fourth place. After winning a fifth European title in January 2017, he faltered at the World Championships in Helsinki. He won the short program, but placed sixth in the free and tumbled to fourth overall. It was the first time since 2012 that he did not stand on a World podium.

“That season was tough for me, right from the beginning. I was training so hard but I couldn’t get everything 100 percent secure,” Fernández explained. “I was fighting all the time in competitions — some of them were great, but some were not the best. At Worlds, I had an amazing short program and I was confident in myself going into the free. But while I was waiting to skate, I heard the scores for Yuzuru and I kind of got scared, and because I was not 100 percent secure, I began to think negatively.”

But not winning the World title also removed a large target from his back, something that was reinforced during a post-Worlds discussion with his coaching team. Fernandez knew it would be a tough year but reasoned that having a little less pressure on his shoulders was a positive.

LAST HURRAH

As he began to prepare for the Olympic season, Fernández adopted a mindset to work hard, defend his European title and head into his final Olympics with a defined plan.

Battling a bout of stomach flu, he opened his season with a sixth-place finish at Cup of China. He won his second assignment in Grenoble, France, claiming his seventh and final Grand Prix gold medal but failed to qualify for the Grand Prix Final. “If that was my last Grand Prix, I am happy I was able to win it. Maybe not with the best performance, but it is a real goodbye to the Grand Prix Series.”

In the four years since his disappointing fourth-place finish in Sochi, many things had changed. Fernández had won two World and four European titles, but what he wanted most was an Olympic medal. He was determined to not let the final opportunity slip through his hands at the 2018 Olympic Winter Games, and in PyeongChang it all came together for the Spanish star.

Second after the short program, Fernández was confident heading into the free. On any other day what he produced — two quads and seven triple jumps — might have been enough to win, but on this night, it ranked only fourth best. He dropped to third in the overall standings but skated away with the bronze medal. It was the first Olympic figure skating victory for his nation and only the fourth medal ever won by Spain at an Olympic Winter Games.

It was an emotional night for Fernández. “I finally got the medal I always wanted. It has been a lot of work and a lot of years to fulfill my dream.”

Throughout his career, Fernández singlehandedly wrote Spanish figure skating history and though being a pioneer was both a burden and a blessing, he set a high standard for those who will come after him. “Being the first person in something is not easy, but it kept me going because every single year I saw improvement. I had an idea that one day I could be World champion. I didn’t know if it was possible, but I just followed my dream. When I took the opportunity to go outside my country and start working with a great coach and train with great skaters, I just tried to follow my dream. It worked.”

In his lengthy career on the senior circuit, Fernández made 13 consecutive appearances at the European Championships and claimed 14 Grand Prix medals (seven of which were gold).

But it was not medals alone that drove him to be his very best. For him, it was always about leaving a legacy, growing the sport in his homeland and showing that no matter where you come from, you can reach the top echelons of the sport.

Fernández proved that all things are possible. You can come from nowhere and be the best. He had worked his way up, improving every year, earning the respect of the judges and the fans along the way.

He now plans to skate in shows for the next couple of years, but his ultimate goal is to develop skating programs in his homeland and help produce the next generation of Spanish stars. In the interim, he will host summer camps and seminars and focus on his show projects. When he finally hangs up his skates, Fernández plans to become a fulltime coach.

“I am not coming back. Maybe I will do a pro competition or Japan Open, but no, I’ve achieved everything,” Fernández said. “I set goals and I’ve achieved them. The Europeans is more my house and I wanted it to be my last competition. It’s time for the next step in my life. I’ll be doing shows, teaching — a lot of other things, but not competing.

“I hope people will remember me as a different type of skater, a more complete skater than the ones we are supposed to be. Skaters are not just jumps, but they are about complete skating. I hope I have left something like that in figure skating. In 20 years, maybe some people will still remember my name, or maybe not. We’ll have to see. But I’m proud of what I’ve done.”

Fernández said after living in Toronto for eight years there are things he will miss. “The people treated me so well. I will miss the Cricket Club and the people that work there, and the skaters at the club. I liked it. It had a lot of good parts of my eight years in Toronto and the people that I met there.”

When asked to name one moment of his career that stood out above everything else Fernández said that would be impossible. “I have experienced so much through my skating that the person I am right now is because of what I have done. So, it would be hard because I have achieved so many goals, done so many competitions, met so many people and traveled to so many places.

“Which one would I prefer? The first Grand Prix in Canada or the first European Championships that I won? The first World or Olympic medal or the seventh European title? What’s better? What to choose? It’s almost impossible. There are so many special emotions. It’s the same if we talk about the programs. Every program, every costume is just a little part of me. It’s all a good memory.” With files from Robert Brodie and Yuan Li

(Originally published in the March/April 2019 IFS issue)