The World Figure Skating Hall of Fame named its 2019 honor list in April. This year’s inductees all hail from regions outside North America.

The World Figure Skating Hall of Fame named its 2019 honor list in April. This year’s inductees all hail from regions outside North America.

Two ice dance teams — one from Russia, the other from the former Czechoslovakia — singles skaters from Slovakia and Germany and a Russian coach are being honored for their personal accomplishments and their contributions to the sport.

QUANTUM LEAP FOR ICE DANCE

When Natalia Bestemianova and Andrei Bukin danced away with the 1988 Olympic title their triumph was the culmination of 11 years of hard work.

Legendary Russian coach Tatiana Tarasova had worked with Bukin since his late teens, and in 1977 decided to pair him with Bestemianova, a singles skater. The opportunity to try ice dance was a blessing for Bestemianova whose former coach considered her untalented and without prospect in singles skating. “It was very difficult for me, from a psychological point of view. Tatiana really breathed life into me,” Bestemianova recalled.

From the outset, Tarasova looked beyond the choreographic mainstream, choosing Soviet ballroom dancers Irina Tchubarets and Stanislav Shkliar to design their programs. The unconventional choreography Tchubarets and Shkliar crafted for the team — throughout their entire career — highlighted the duo’s strong technique, remarkable unison, and Bestemianova’s rubber-like flexibility.

Bestemianova and Bukin placed 10th in their international debut at the 1979 World Championships, and just three years later were battling it out for top honors with Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean. After claiming bronze at Worlds in 1981, the Soviet duo danced into second place behind Torvill and Dean at the next three consecutive World Championships, and also at the 1982 and 1984 European Championships. The only major competition the Soviets won in that three-year period was Europeans in 1983, which Torvill and Dean did not contest. Bukin described the win as the highlight of his career. At the 1984 Olympic Winter Games in Sarajevo, the Soviet team placed second once again behind their British rivals.

But everything changed when Torvill and Dean retired. The following season, the Russian duo mined gold at 1985 Europeans earning seven perfect 6.0’s for artistic impression. It marked the beginning of a new era for the team — it was the last competition Bestemianova and Bukin would ever lose in their amateur career.

Their theatrical programs had captured everyone’s attention, but not all were in favor of the avant-garde approach. “Critics of many countries referred to our performances in this way,” Bestemianova recalled. “In 1985, Andrei and I lost all national competitions because of too much theatricality in our ‘Carmen’ program. But it’s simply how we saw dance on ice and we could not do anything differently.”

In 1986, the Soviet team received four perfect 6.0’s for their performance to a Rachmaninov piano solo, en route to winning their third European title. A year later they went in a completely different direction with a comedic routine set to music from “Cabaret.”

For the 1988 Olympic season Bestemianova and Bukin returned to a dramatic theme with Alexander Borodin’s “Polovtsian Dances” from the opera “Prince Igor.” Toller Cranston, in his commentary at the 1988 European Championships, criticized the team’s free dance costumes, but acknowledged, “they were certainly deserving of the European title.” (Bestemianova and Bukin received 5.9’s across the board for technical merit and seven 6.0’s for artistic impression).

The atmosphere in the arena the night of the free dance at the 1988 Olympic Winter Games in Calgary, Canada, was electric. Bestemianova and Bukin put down a free dance that Dick Button described as a “quantum leap forward in ice dancing. I think it is very clearly in the tradition of a new kind of ice dancing — theme dancing,” he told millions of television viewers. Bestemianova and Bukin scored 5.9’s across the board for technical merit and three 6.0’s for artistic impression. The only dissenter on the second mark was the West German judge, who gave them a 5.5.

Tracy Wilson, the 1988 Olympic and World ice dance bronze medalist with Robert McCall, cited her Soviet contemporaries as a major influence as she and McCall rose through the ranks. “I would just be blown away every time I watched them … and love every minute of it,” she said. “I felt like I had a better appreciation of how regimented the discipline was technically, and I learned so much from her that brought more joy to my own skating.”

Three weeks after claiming Olympic gold, Bestemianova and Bukin captured their fourth and final World title and retired from the competitive ranks. In an ironic twist, Betty Calloway, the former coach of Torvill and Dean, was at the boards for the Soviet duo at this competition.

Bestemianova and Bukin will also be remembered for sparking the controversy that erupted over skaters “dying” on the ice. The dramatic final death move of Torvill and Dean’s 1984 “Carmen” program started a new trend. Suddenly, skaters from all disciplines started “dying” on the ice.

But the Soviet team took it to the extreme and when Bukin died four times during an exhibition program, the International Skating Union (ISU) said enough. Dying or lying on the ice was henceforth forbidden.

Nonetheless, in 1992, the ISU awarded Bestemianova and Bukin the Jacques Favart Trophy for their innovations and contributions to the discipline.

Though Soviet ice dance teams were not in high demand for skating shows in the 1980’s, the duo scored a contract with Tom Collins’ Tour of World Figure Skating Champions. Their contract ran from 1982 to 1988, and they closed out their career with one last tour in 1991.

Five years earlier, Bestemianova and Bukin had signed on with the Bobrin Ice Theatre, Moscow Stars on Ice tour, founded by 1981 European champion Igor Bobrin. “There were so few professional competitions for ice dancers, so we had no choice but to turn in another direction,” Bestemianova explained. “When we first started performing with ‘Ice Theatre’ it only toured in the Soviet Union, but in 1988 things changed.”

After a successful European run, the tour expanded and for almost two decades it played out in Asia and the Americas. Bestemianova was the producer, designer, costumier, and the star of the show.

Bestemianova, 60, has been married to Bobrin since 1983. The couple has no children but Bobrin has a son, Maxim, a surgeon, from a prior relationship. Bukin, 62, has two sons — Andrei, 36, (with his first wife Olga Abankina) and Ivan, 25 (with his longtime partner Elena Vasyukova), who was also a competitive ice dancer.

In March 2017, Bestemianova and Bukin celebrated their 40th anniversary as a team.

UNHERALDED CHAMPION

Though 46 years have passed since Ondrej Nepela claimed his third and final World title, no skater from his homeland has ever come anywhere close to matching what he achieved during his career.

Though 46 years have passed since Ondrej Nepela claimed his third and final World title, no skater from his homeland has ever come anywhere close to matching what he achieved during his career.

Born in Bratislava, Slovakia (formerly Czechoslovakia), Nepela began taking lessons at the Slovan Figure Skating Club at age 7.Two weeks later his mother attended a session and asked Hilda Múdra, a coach at the rink, why her son was not learning any tricks. She then handed Múdra two jars of jam with a request that she take over coaching her son starting the next day. Múdra agreed. It was the beginning of a lifelong connection.

A week after his 13th birthday Nepela competed at his first major international competition, the 1964 Olympic Winter Games, where he finished 22nd. Two years later, he claimed the first of three consecutive European bronze medals (1966-1968). His eighth-place finish at the 1968 Olympic Winter Games marked a turning point in his career. It would be the last time Nepela did not stand on a podium.

In 1969, he claimed the first of five consecutive European crowns and two years later won his first global title.

At his third and final Olympic appearance in Sapporo, Japan, in 1972, Nepela produced outstanding compulsory figures that had him in a virtually unbeatable position. A fall on a triple toe loop in the free skate left him in fourth-place in the segment, but the judging panel unanimously placed Nepela first overall. He remains the only person from his nation to ever win an Olympic figure skating title.

Known for his elegant spins and consistent jumps, Nepela’s greatest weapon was the control he had over his nerves in the heat of competition. In his 2000 autobiography, “When Hell Freezes Over, Should I Bring My Skates?” Toller Cranston recalled his rival as “a steady, nerveless competitor, completely lacking in personality or finesse: a generic Soviet-satellite skater who had been browbeaten into becoming a fine technician — less fine in free skating and more precise or womanlike in school figures.”

Following his Olympic victory, Nepela wanted to retire from amateur competition, but with Worlds taking place in his hometown the following year, he decided to remain eligible for one final season. He claimed his third and final World title in Bratislava and immediately turned professional. Nepela spent the next 13 years touring with Holiday on Ice.

In 1986, he relocated to West Germany to take a coaching position. He was subsequently diagnosed with AIDS-related throat cancer and less than two weeks after guiding Claudia Leistner to the 1989 European title, Nepela passed away in Mannheim, Germany, at age 38.

In December 2000, seven years after Slovakia and the Czech Republic became separate nations, Nepela was named Slovakia’s athlete of the century. Múdra accepted the President Rudolf Schuster award on Nepela’s behalf. “He was not as talented as he was diligent and obedient,” Múdra recalled. “I trained him for 15 years from start to finish, and he always obeyed. He was humble and well behaved.”

During his career with Holiday on Ice Nepela had amassed a small fortune of more than $2 million dollars. He stored the money and his personal valuables in a bank safe. Only two people had access to it: Nepela and his financial advisor. When Múdra opened the safe following Nepela’s death it was empty except for one golden skate. His financier had stolen everything. The German government eventually recovered the stolen property.

In 2003, Nepela’s biography, “When the Sky Freezes Over, Do You Put on Divine Skates?” was published in Slovakia.

OLYMPIC HONORS

Yelena Tchaikovskaya competed for just four years domestically, winning the 1957 Soviet Championships in her second appearance. She retired in 1960.

Born into a family of actors, Tchaikovskaya appeared in seven movies during her youth. She graduated from the ballet master faculty at the Russian Academy of Theater Arts in 1964 and later that year turned to coaching and choreography. In 1976, Tchaikovskaya’s students,

Lyudmila Pakhomova and Aleksandr Gorshkov, claimed the first Olympic ice dance title, and four years later Natalia Linichuk and Gennadi Karponosov repeated the feat.

Tchaikovskaya also coached Lithuanian ice dancers Margarita Drobiazko and Povilas Vanagas (2000 World bronze medalists), and singles skaters Maria Butryskaya (1999 World champion), Julia Soldatova (1999 World bronze medalist), Viktoria Volchkova and Sergei Davydov.

In 2007, a documentary about her life, “Her Ice Majesty, Elena Tchaikovskaya” was released in Russia. She is the author of four books on the sport: “Patterns of Russian Dance” (1972); “6.0” (1980); “Figure Skating” (1986); and “A Skate of Luck” (1994).

Six decades later, Tchaikovskaya, who turned 80 in December, still runs a skating school at the Yantar Sports Center in Moscow, where she coaches in collaboration with her former student Vladimir Kotin, a four-time European silver medalist (1985-1988).

Tchaikovskaya has been married to Anatoly Tchaikovsky for more than 50 years. She has a son, Igor Novikov, from an earlier relationship.

TRAILBLAZER

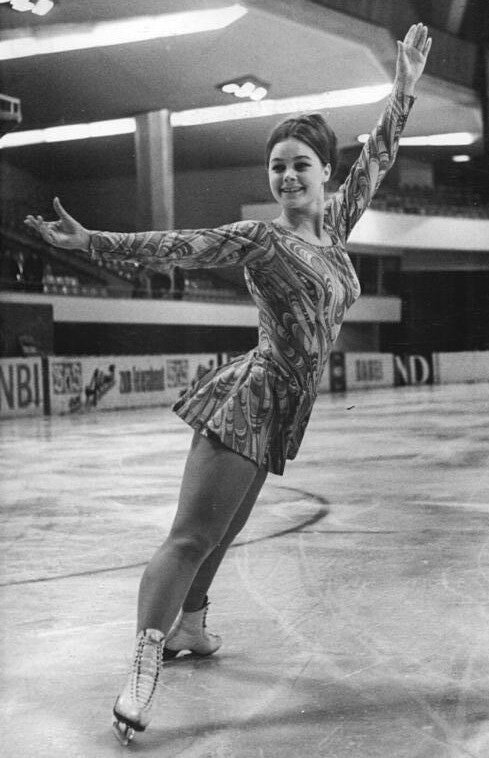

Gabriele Seyfert, East Germany’s first female figure skating star, holds the honor of being the first lady to land a triple loop jump in international competition.

Gabriele Seyfert, East Germany’s first female figure skating star, holds the honor of being the first lady to land a triple loop jump in international competition.

Seyfert emerged from behind the Iron Curtain to claim two World titles (1969, 1970), three European crowns (1967, 1969 and 1970), and Olympic silver in 1968.

Born in Karl-Marx-Stadt (now Chemnitz), Seyfert began skating at age 4. In 1961, the then 12-year-old won the first of 10 consecutive national titles and was sent to the European Championships in West Berlin. She placed 21st in a field of 24. Throughout her career Seyfert was coached by her mother, Jutta Müller, who would years later guide Katarina Witt to two consecutive Olympic titles.

Following her retirement in 1970, Seyfert was forbidden by the East German government to skate in professional shows outside the country. Instead, she was assigned to coach a rising young star named Annett Pötzsch. Like Seyfert, Pötzsch was sent to the 1973 European Championships at age 12. She finished eighth in Cologne and 14th at the subsequent World Championships. “It was fantastic to skate with some of the best at such a young age,” Pötzsch recalled. “My idol then was my coach Gaby Seyfert who had won Europeans and Worlds a few years before.”

When Pötzsch was transferred to Müller’s group, Seyfert retired from coaching. In 1985, she became the director of an ice show at the Friedrichstadt-Palast in Berlin, where she also performed through 1991.

Seyfert married her first husband Eberhard Rüger, a former ice dancer, in 1972. The couple welcomed a daughter, Sheila, two years later and divorced the following year. Seyfert married her second husband in 1978 and the couple settled in Berlin. That union ended in divorce in 1992. She wed her third husband in 2011.

Throughout her life, Seyfert has been identified by many sources in Germany as being an informant for the Stasi (the East German secret police), a claim she has always steadfastly denied.

SIBLING STARS

Eva Romanová and Pavel Roman, a brother and sister ice dance team, hailed from Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. The duo began their figure skating career as a pairs team but switched to ice dance in 1959. They competed in both disciplines at the 1959 European Championships, placing seventh in ice dance and 12th in pairs.

Eva Romanová and Pavel Roman, a brother and sister ice dance team, hailed from Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. The duo began their figure skating career as a pairs team but switched to ice dance in 1959. They competed in both disciplines at the 1959 European Championships, placing seventh in ice dance and 12th in pairs.

In their fourth appearance at Europeans in 1962, Romanová, 16, and Roman, 19, finished third. Two weeks later the siblings upset the establishment by winning the first of four consecutive global titles in their debut at the World Championships, which took place on home soil in Prague. They became the first non-British team to win the title and remain the only World ice dance champions to ever emerge from Czechoslovakia.

At the 1963 Europeans, the scores were so close after the free dance that it took an hour to tally the results to determine which team had won. Romanová and Roman placed second behind Linda Shearman and Michael Phillips of Great Britain. It was the last competition they would not win. A similar scenario took place at the World Championships, where, after 40 minutes of tallying the scores, the Czech duo claimed the crown by a one-point margin over the same team that had beaten them two weeks earlier in Budapest.

Finally, in their fifth appearance, the siblings captured the first of two consecutive European crowns. The highlight of their free dance that year was Romanová executing a sequence of lightning spread eagles between turns on her toe picks. Unlike the scenario that played out a year earlier, their victory at the 1964 World Championships in Dortmund, Germany, was unanimous.

In 1965, Romanová and Roman claimed their second and final European title in Moscow. They closed out their amateur career at the Broadmoor Palace in Colorado Springs, Colorado, with their fourth and final victory at a World Championships.

The siblings retired from competition and toured with Holiday on Ice for six years. Romanová married Jackie Graham, an English comedian. The couple lived in the U.S., eventually settling in Great Britain. Widowed at 46, Romanová resides in the village of St. Anne’s outside Manchester. Roman also moved to the U.S. Six days after his 29th birthday in 1972, he was killed in a tragic accident when his car struck a tree in the state of Tennessee. He was inducted posthumously.

(This article was originally published in the August 2019 issue of IFS)